I’ve talked a little about Targets Per Route Run (TPRR) in the introductions to Stealing Signals each week, but it’s not a stat I’ve gone through extensively in the weekly writeups. And that’s because targets can be highly variable weekly, and we want to build a decent sample. But I was reminded this morning by a series of cool visualizations from Establish The Run that I wanted to circle back on this after a couple of weeks.

If you’re not familiar with the stat, TPRR is basically the driving force behind it’s more popular counterpart Yards Per Route Run (YPRR). And in a follow-up post I’m going to go team by team and give you some early-season TPRR takeaways. I put that one behind the paywall simply because I refer to so much that I wrote in Stealing Signals this week and frankly I agree with the feedback I get from paying subs that the information they pay for should mostly stay behind the paywall.

I do real quickly want to discuss a few players from this week’s Stealing Signals here. I got some questions about Darrell Henderson and then also how Brandon Aiyuk fits in with popular Week 3 breakouts Tee Higgins and Justin Jefferson. And it made me realize I was assuming a bit too much.

In Week 2 Stealing Signals, Henderson was one of the top Signals in the weekly recap. I wrote that he might be the workhorse going forward. Operating from those high expectations, my Week 3 writeup on him was more subdued, noting he wasn’t exactly a three-down back. I remain very high on him overall.

Similar applies to Aiyuk, who was a key Signal in the Week 2 recap for his 80% routes per dropback in his Week 2 debut. We needed to see him get some actual touches in that massive role, which I’ll talk about more below. But to clarify where I stand on him, I made a claim for Aiyuk in a shallower league last night ahead of Higgins and Jefferson. (I’d already added him the week before in a couple other shallow leagues, and have him stashed elsewhere.) And then I had Higgins over Jefferson, mostly due to offense because I liked Jefferson quite a bit more as a prospect. That might be a mistake, but man there’s a lot more opportunity in that Cincinnati passing game.

But I just want to reiterate, if I gloss over someone a bit, it could very well be because we already touched on him a week early, and I’ve recalibrated my expectations to what we discussed the prior week. It’s going to be something of a regular occurrence because the shiny new things of the week are the focus of the writeups, and I frankly don’t always think (or want) to write “I told you to stash Aiyuk last week and this breakout was not surprising.” But that doesn’t mean if your waivers run tonight and a guy like Aiyuk or Henderson is available this week that I’m not making them a priority — I very much am.

Background on TPRR

Back to TPRR and some background on why you should care about it. Over the past few years and then this offseason especially, YPRR gained a lot of traction in the fantasy community as a hot new stat. One thing that is often cited is that it is a more predictive “efficiency” stat. In fact, when I cited Yards Per Target (YPT) a couple of times, specifically I recall doing so once about O.J. Howard when the point was very specifically that he’s been very good when he earns a target, I got quite a bit of feedback from random Twitter accounts that I didn’t know what I was talking about and YPT was terrible compared to YPRR.

That’s always a funny part of the gig, and is typically the result of someone in the industry having recently compared the two in an article or on a podcast somewhere and then a subset of fantasy-engaged Twitter users who caught that piece of content not thinking critically themselves but rather being stoked that they know something someone else doesn’t. And I’m not saying that because they came at me specifically — this happens legitimately all the time. The point to take away from this story is it’s pretty commonly understood that there is a lot of groupthink in the fantasy community, and this is a great example of how that happens. It’s not just player takes where groupthink can form; it can be how the whole industry seemingly ebbs and flows on its process and use of specific stats as one giant entity.

Understanding nuance like that is an opportunity. There’s the old idea that all clothing styles come back into fashion after a few decades, and there are absolutely points at which I’ve eschewed advanced stats for good ol’ fantasy points or something seemingly basic like targets, because suddenly the obvious in a situation is no longer en vogue. While we’re still not where we can be in terms of football stats and analytics generally, there is a ton of new stuff popping up all the time that is both very useful and also hard to parse for the average fan. There are no perfect stats, but a ton of them, and I’m in no way arguing they are all bad, but people have a desire to feel informed so they latch onto things. In that setting, interpreting what is actually useful in a given situation — cue up the signal/noise reference — becomes the real skill, far more valuable than chopping up data or repeating the cool stat that has been recently referenced.

At any rate, I will cop to getting annoyed at the YPRR and YPT comparisons in my mentions this offseason, not because I think YPT is a great stat, but because the difference between the two stats is simply Targets Per Route Run (TPRR). Put differently, YPRR can be broken down into two component parts, YPT and TPRR. Here’s a very simple way of writing that where middle school algebra tells us we cancel the targets and wind up with YPRR.

(Yards / Targets) x (Targets / Routes Run) = (Yards / Routes Run)

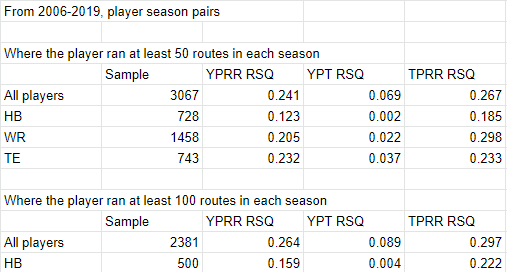

So if YPRR is better than YPT in all research, and YPT sucks, logically that would be because TPRR is the useful stat. So I tested that — I pulled a bunch of data, made a spreadsheet because I’m a broke ass coder, and tested the year over year stability of the various component parts. And wouldn’t you know, TPRR is the much more stable element. I wrote about it in a Twitter thread that included some of the results and also referenced work from several years ago where the efficacy of TPRR had already been shown.

This last point about targets being earned is I think the key one. Whether we called YPT, YPRR, or TPRR efficiency stats is a weird discussion about nomenclature. Traditionally, pass-catcher “opportunity” has referred to targets, while “efficiency” has referred to things like catch rate, yards per reception or target, YAC, etc. Thus, YPRR isn’t even really an “efficiency” stat because what it’s adding is a form of target rate, and we’ve known targets to be a much better indicator of fantasy success than efficiency metrics for many years.

But the whole idea of TPRR as a stat flips that on its head anyway. If TPRR specifically is a useful stat that helps drives our understanding of fantasy production, then whether a player sees a lot of targets per route run is a differentiating skill, which is basically how you define efficiency. A player earns his targets, they aren’t handed to him. The route is the opportunity stat.

This creates a third layer. Rushing numbers can be easily split as opportunity (how many times the ball is given to the player) and efficiency (what happens when the ball is given to the player, which can include offensive line play and more), like fantasy analysts have done for years. But receiving numbers can’t be as cleanly split.

Snaps and routes are the first element, the pure “opportunity” one.

Then, an ability to earn targets is more skill-related than how it is traditionally discussed.

Finally, an ability to actually catch the ball and do good things like score touchdowns is still further removed from that.

And these last two are also impacted by the depth of the route/target, which is something that shouldn’t get lost here. But the end result is players can fail three ways — there are players who get a lot of targets but aren’t very good (Chris Conley last Thursday night!), players who run a lot of routes but don’t earn targets (Chris Conley his whole career!), and players who aren’t even seeing the field (Chris Conley going forward if we’re lucky!).

Chris Conley jokes aside, typically players fall into one of these buckets, and those classes of players should all be viewed differently. Conley, for example, would fall in the second bucket — that’s been the story of his career, and it basically precludes him from ever being more than a mildly useful fantasy piece like he was in 2019 when he had a career year in basically every respect. He’s never going to be a top player.

But players who are seeing a lot of targets but aren’t very good are more likely to rebound, as the YPT or YPR type stats are notoriously unstable. That doesn’t mean they will, because some players are just bad.

And players who aren’t seeing a lot of raw targets because they aren’t even seeing the field, but do see targets when they get some reps, are another interesting upside case.

So I’m currently writing up a post going through each team, which will come in the next hour to talk about some interesting early-season TPRR rates in the context of how much guys are playing and how they are performing. If you haven’t subscribed yet, you can do that now.