Reviewing 2022 projections can highlight recurring mistakes

An in-depth look at what we thought last summer

It’s that time of year again where I discuss my skepticism of full-season projections, but also explain why I still do them every year, and will probably never stop that process because I do get so much out of it. I’m never arguing there is no value to be taken from the process, but rather that the market at large overplays the results.

If you have followed my work in the past, you know I sometimes reference off hand how projections “will love” (or perhaps hate) some player. When you’ve done the process long enough, you know there are certain realities that it will push you toward, no matter how much you want to make a stand.

If you start projecting things way out of line with market assumptions on a team or player — just to take a stand so that you’re not making a “mistake” you think you’ve identified — you can skew the results in several different ways. Team-level volume assumptions can push you higher than market on several of a team’s players. More volume to a skill position player can negatively impact what’s available for all his teammates, since good projections need to add up on the team level. Or spiking the efficiency for a player — say his receiving TDs — may lead you to career-high passing efficiency for his QB.

As I go through my 2022 projections, I have this note highlighted in red on the Eagles’ page, the only such-highlighted note I could find in the whole document:

Apart from being a frustrating reminder that things would have been better if I only hadn’t been so latched onto Trey Lance at a cheaper price, this is why sometimes projections are fantastic. Adding A.J. Brown to an already strong receiving duo did have an extremely positive impact on Jalen Hurts’ passing efficiency last year, as many expected. Hurts averaged 8.0 YPA after seasons of 7.2 and 7.3, and his TD rate was a career-high 4.8% after sitting at 3.8% through two seasons.

This is one of those things that feels more obvious in hindsight, but it’s a great example of the push and pull of projections. First, I would argue past data is simply a guide — descriptive data that helps us predict forward, but you’re still tasked with forecasting to get the best/most accurate projections you can get (even if those won’t wind up being that accurate). So many analysts in this industry treat past data as the only (or main) piece of information in predicting next season. “I can’t believe this player is going at [ADP], he went [statline] over [time period]” isn’t sufficient analysis.

Relatedly, Hurts’ statistical improvement was big enough to be difficult to project; it’s an example of how league-winning types often produce what I call “unprojectable” stat lines. As my note in red above indicates, it was not comfortable to project Hurts to take a huge statistical step forward. I had him at a 7.6 YPA and 4.7% pass TD rate, in part because all roads leads to A.J. Brown, but if you were getting Hurts anywhere close to his eventual 8.0 YPA and 4.8% TD rate — and then doing your cross-checking diligence — you were probably putting a note in red like mine above.

As I’ll show, being out on a limb like that can be beneficial but also harmful. More importantly, if you wanted to project Hurts that aggressively… you probably didn’t even need to do a projection set. There was a lot that could be learned from doing the Eagles’ projection, but at the same time the specific numbers didn’t really matter if your take was fairly simply that A.J. Brown was going to be the wind beneath the wings of the Eagles’ passing game, and Hurts was going to be in the MVP conversation. You could have been in on that stance without projecting anything, and been all over Hurts at his ADP last season.

But if you do want to make projections, or value them, and you’re trying to get them as accurate as possible in a way that accounts for a lot of potential outcomes and either averages them or lands close to a median, you do have to grapple with the types of second-order effects of every decision you’re making that I described above. It’s both a feature and a bug of projections. It’s a feature because guardrails exist, and good projecting does show you where there are statistical limitations, either where something big needs to happen for a specific ceiling or floor outcome, or how a whole range might be higher or lower than it feels. Anyone worth their salt can see in their results when their optimism pushes credulity relative to things like Vegas win totals and ADP expectations, since we know markets are strong.

But some people will blow by those red flags and confuse that analytical recklessness with confidence (and I’ve written before how we as humans are attracted to confidence — it’s fun!) but projections done that way are frankly a waste of time. As I said above, you might as well just say “I’m super high on Jalen Hurts!” and be done with it; no point putting some massive numbers by his name because the specifics won’t really change that you should draft him at ADP.

And that’s the bug of projections, or an extreme version of it. Even if you’re careful, projections can lead to false confidence, and perhaps especially for those people who don’t blow by red flags and take into account every little detail and note that they come across all offseason. Projections are typically something of a Week 1 snapshot more than an accurate portrayal of a full season, because the rule in the NFL is always chaos, so it’s important to understand projections are an idea of what can happen — and can inform us on multiple scenarios from floor to ceiling — but then we need to use critical thinking to consider even the most extreme outcomes, which in many cases define seasons (Atlanta’s pass volume last year being an unprojectably poor outcome comes to mind as the flip side of my earlier point about league-winners having unprojectably lofty statlines).

So before I get to the next part, and as we undertake a series of posts around projections for the next few weeks, a few things I want to drive home that I believe to be pretty strongly true:

Projections are valuable, and done right, they can even account for more than just one potential outcome for a team. But even still, there is a ton of uncertainty baked in, so how we apply those end results is key.

If we simply took all projection sets that were reasonable, or “good” — that weighed market forces and were respectful of the data and information we know, but also made the human assumptions that have to be made — they will be reasonably similar. The gap between optimistic and pessimistic sets of a specific team’s projection will be vastly narrower than the actual potential results. (A big reason I can say this confidently is I’ve done the projections comparison podcasts with now three analysts whose work I really respect — Michael Leone most recently, Heath Cummings during my time at CBS, and initially Pat Kerrane back at RotoViz — and they all have slightly different processes and my own process has evolved, and yet I’m always amazed how close we wind up on so many different elements.)

To the point about the actual potential results being a wide range — it is a known that there will be outcomes that stretch what is reasonably projectable. And those outcomes very frequently define fantasy football seasons.

A huge part of this preamble is to establish the case that my projections, while certainly not amazing and definitely not what I’d call the best in the industry, are probably “good enough” to serve as a proxy for a backward-looking accuracy check. I’m pretty careful — I tend to run a bit hot where all my projections are a little more optimistic than makes sense, e.g. something akin to a 60th percentile outcome, but I find it easier to project while assuming some reasonably favorable stuff.

But overall, the projections are within the realm of solid projections, and those of you who listened to the podcast series with Leone last year — and who know I think of Leone as the industry standard for projections because of how well he incorporates all elements — will know I was thrilled to see a lot of my assumptions and specific numbers were pretty close to his. It’s not like I’m way out on a limb on all this stuff.

And I’m establishing that because I want to review my 2022 projections, as the title indicates. In 2020, while still at CBS, I reviewed my 2019 projections solely on the team level. It’s a piece I’ve referenced perhaps more than any other since that offseason, and yet it’s not research I’ve done again. (Why? Because it’s tedious. Who wants to spend hours of their time reviewing past analysis? Still, I’m kind of shocked we don’t see this kind of things more, because it’s also super valuable. There’s just so much that can be taken from it, and engaged people really love thorough research, which I’ve learned time and again from my work on Stealing Signals.)

The reason I’ve referenced that old CBS piece so frequently is I was shocked to learn how poorly my projections did just on team volume alone. Here was one of my big takeaways the last time I did this.

For exactly half the teams, my projection was at least 50 plays, passes or runs away from the actual observed outcome. That's a ton of missed opportunity, and it reinforces the clear takeaway — I shouldn't be too sure of any of the assumptions I made in my 2020 projections.

That’s right, for 16 of the 32 teams, I was way off on something that significantly impacted the team-level volume, which in turn significantly impacted the player level. When I say my projection was off by at least 50 plays, it’s important to recognize that the range of viable outcomes is typically about 200-300 plays from league low to league high, for each of the big three team-level categories discussed here: total plays, pass attempts, or rush attempts. Being off by 50 implies a range of 100 (50 above and below my number) and my projections are frequently regressed toward the middle of that range. I knew I would be off on a lot of these, but I would have guessed that because some of the teams feel clear in terms of being higher or lower than league average in certain ways (think slow, run-heavy teams versus pass-happy, fast-paced ones), that I could have at least put a pin somewhere in this 250-300 unit range that would have been within 50 of each of the three categories for more than 16 teams.

To put some 2022 numbers to those ranges, last year Carolina ran the fewest plays in the league with 976, and Tampa Bay ran the most with 1159, which was a gap of only 183 plays. If you go look at my projections, I missed by plus-or-minus 50 plays on eight teams, and my projection for all eight was between 1050 and 1100 plays, right around a reasonable midpoint for the actual results. Plus-or-minus 50 plays from a projection of, say, 1075 creates a range from 1025 to 1125 — 100 plays wide — right in the middle of that 183-play range of actual results I mentioned from Carolina to Tampa Bay. And obviously there are extreme outcomes, but Tampa at the very top isn’t even one of the teams I was off by 50 plays on, because they are an example of one I did project to be among my highest-volume teams in the league.

One of the really useful parts of this type of backward-looking analysis is to see if the areas where I did diverge from market projections were smart or dumb — did taking a stand improve my success rate or get me out on a limb that reduced my accuracy? One quick and easy way to look at that is offensive touchdowns.

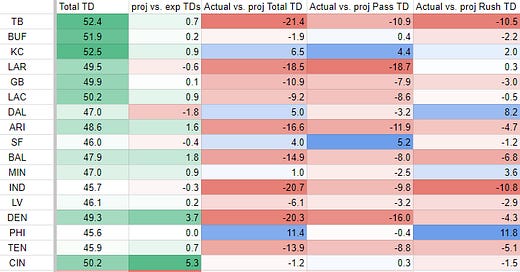

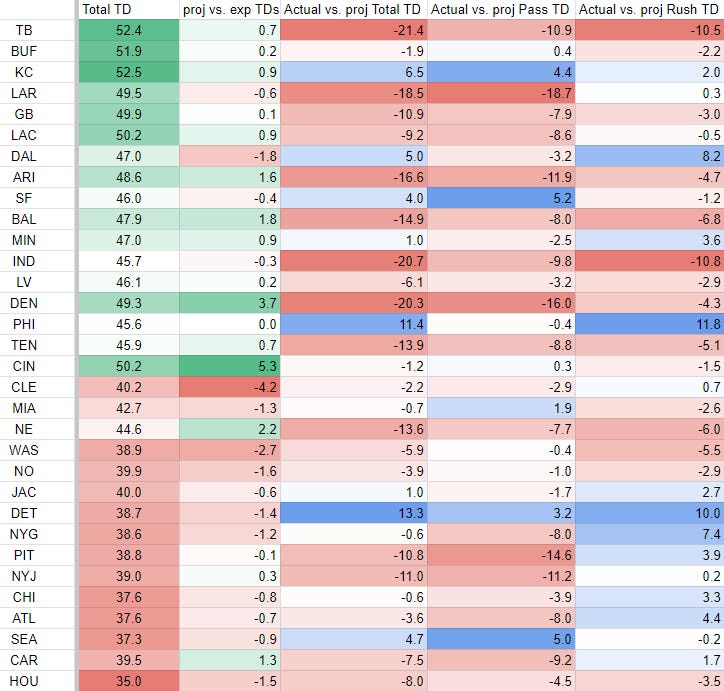

In a second I’m going to show a quick table that shows a few things. The first two columns are from my projections, and are one interesting thing to look at because they show which teams I was higher or lower on. The teams are sorted by implied team totals from lookahead lines for last season, going into the year (hat tip a tweet from 4for4 analyst Connor Allen for those numbers).

I used Connor’s numbers to make a rough “expected TD” figure for each team that matched the implied totals, and the second column below is my actual projection versus what the market suggested for those teams. I was highest above market on Cincinnati, projecting them to score 5.3 more touchdowns than the Vegas lookahead spreads implied, and that was a good stance to take. But my next highest stance was on the Broncos, so you win some and you lose some. Overall, I was pretty balanced.

The next three columns in the table below are all calculated after the results were in. I wanted to keep these side by side so you could see where my projections were optimistic or pessimistic and how that influenced the final three columns, but the final three are themselves pretty self explanatory — it’s the actual results versus what I projected (red means I projected “hot,” i.e. too high, while blue means I came in under the actual result).

Right at the top we see that going into last year, Vegas lookahead spreads had the Buccaneers as the highest-scoring team in the entire NFL. I projected them essentially that high, but my projection was too high by a whopping 21.4 touchdowns, evenly split about 10 each on both the passing and rushing side.

Here are some other quick notes:

Overall scoring was down, so I came in too hot for far more teams than those I underprojected.

For teams like the Rams, I was way off due to injury. I had Matthew Stafford tied for the fourth-most passing TDs of anyone in my projections.

He was tied with Joe Burrow, and my optimistic projection of the Bengals — and particularly being above market on their passing TD rate — was nearly perfect.

I had Russell Wilson eighth in passing touchdowns, and my optimistic projection for the Broncos was not just wrong — they went way below market, and I was over market on them, so it was way off. This is a great example of the potential harm in being out on a limb, ahead of (or behind) market. When I do my own projections, years of this type of learned experience keeps me (somewhat) checked.

I actually projected the Colts a little light relative to their range of teams in the Vegas lookahead projections, but they are another team where their actual result was more than 20 TDs lower than projection. I was particularly pessimistic on the passing game, still projecting Jonathan Taylor for 16 total touchdowns, and I was correct to be light on the pass TDs but overstated Taylor’s ability to succeed despite surroundings.

I was on the Eagles’ passing touchdown bump, but was way low on their rush TDs which was probably one of those unprojectable outcomes on the team level given they ran for 32 scores.

There’s a sweeping actionable thing here where I have expected pass rates for these teams based on market expectations, and bad teams are expected to pass more, but universally I wound up with more pass TDs than bad teams actually threw for, and I correspondingly wound up with fewer rush TDs for those teams. So the note for me is “bad teams rush for TDs, too,” and that the bad offenses are probably worst for passing because the QBs are so frequently the issue.

Despite being below the bottom of the scale on the Texans, I still somehow overprojected them by eight touchdowns, a reminder of how bad situations can be even when you thumb the scale on projections.

There are obviously a ton more specific notes that could be made, but the biggest takeaway for me is the broad one: humility. Most of these are not just off by a little, but meaningfully off. One thing I’ve always considered with projections is how fickle the end results can be, in terms of worrying about ranking the players. In many cases, a half-percentage bump or decrease in touchdown rate can move a player up or down five or more slots. Suddenly a guy goes from looking like borderline top-10 WR to looking more like a mid-level WR2, with the obvious implications of how that translates to ADP, and it’s all because of a super inexact science where we’re looking at some unclear past data (stuff like whether D.J. Moore’s past TD rates mean he just really can’t score TDs is always in play) and also aren’t projecting the team-level factors particularly well.

That’s not fair, actually. I think the market actually does do a good job of projecting the team-level factors, in terms of predicting what is most likely given what we know entering the season. The problem is again that chaos is the rule, right? There is uncertainty, and things happen. And so ultimately, the reality that the final results will differ from expectations meaningfully in a number of situations is just a key thing to keep in mind when you consider how tight the margins can be between players in final projections. There are so many levers to pull to get to those final projections, and the odds that at least something among those levers will be meaningfully inaccurate for some foreseeable reason — whether that’s team-level, player efficiency, teammate issues, what have you — is high. For a guy like Josh Jacobs, my takeaway has been that he both consolidated volume and also was far more efficient than was projectable, so you’re talking about unprojectable outcomes on multiple fronts (which isn’t meant to minimize the hit but rather contextualize what we’re looking for).

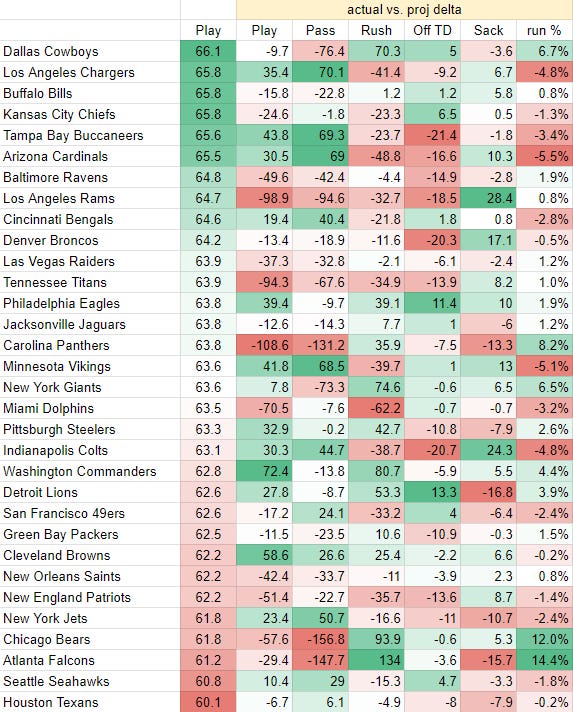

Alright, let’s do team volume and then land this plane. The teams are sorted by my projected play volume, so you can see who I had as slow and fast paced, and the first column is plays per game. The next several are all my projections versus the actual results, and these are not per game but rather full-season numbers. The final column is rush attempts divided by total plays (which is just how I’ve always had pass rate in one portion of my projections for like a decade).

I didn’t want this to be too unwieldy of an image, so again these are just how much I missed by. The negative (red) numbers are where I projected too high. For the Bills and Bengals, I modified my per-game projections down to the 16 games they played, and the difference between actual and projection reflects that.

Some thoughts:

I was more than 50 plays heavy on the projections for:

Panthers (the mild optimism for Baker Mayfield was unwarranted)

Rams (Stafford injury)

Titans (turned into a mess)

Dolphins (were weirdly slow-paced in part due to their own efficiency at times, and then other times just bottoming out with Tua Tagovailoa hurt)

Bears (ridiculous pass rate)

Patriots (the Matt Patricia thing didn’t work)

And I was more than 50 plays light on projections for:

Commanders (actually played faster and were more fun than their win total, which is something Ron Rivera teams sometimes did in Carolina and is a fun note to think about if Sam Howell has some juice)

Browns (Deshaun Watson suspension wasn’t even finalized when I did this, so that projection assumed he wouldn’t play at all and it would be close to a disaster, but interestingly they were actually solid with Jacoby Brissett and that disaster idea wasn’t right)

In addition to those eight teams where my play volume had me meaningfully off on rush attempts, pass attempts, or both, I was meaningfully off on rush and/or pass attempts but not play volume for:

Cowboys (close on play volume, but about 70 plays too pass heavy)

Chargers (one of just five teams where I projected them to record rush attempts on fewer than 40% of their plays, but I was still nearly five percentage points too high on rush rate and way low on pass attempts)

Buccaneers (like the Chargers, historic pass volume)

Cardinals (Kyler Murray injury shifted them toward more losing and fewer QB runs, so pass attempts were light)

Vikings (again light on pass attempts as they played a wild schedule of close games with tons of passing late)

Giants (close on play volume, about 70 plays too pass heavy)

Lions (a little more than 50 rushes light, largely due to them being better than expectations and being in position to run more)

Jets (about 50 pass attempts light, which is kind of funny when you consider their Zach Wilson splits)

Falcons (vaguely close on play volume, but nearly 150 pass attempts too heavy, which was hilariously not the biggest gap since I overprojected the Bears even more)

That makes 17 teams this time around that hit my arbitrary cutoff of plus-or-minus 50 total plays, rushes, or passes. Last time I did this all those years ago, I didn’t look at offensive touchdowns, but I feel like that analysis just drove home how when the team volume is wrong, all the other things in a projection that rely on that can cause things to spiral the further down you go. What I mean there is if I had it in me to do a really deep dive on the player level, I think I’d find even wider ranges, because there are so many more assumptions that can be misses and we already know the team-level stuff was off for more than half the league.

So why am I still going to spend about an hour per team projecting all 32 over the next month or so? Because the process still highlights things, and we’re still trying to make our bets with the information we have now. The teams where I missed because of major injuries like the Rams — that’s not an issue with projections. Cooper Kupp was smashing when he went down, and I’m fine with my take last year that he should still have been WR1, even as that played out in the almost cliche way where the older player got injured and the exciting young debate competitor smashed, too (I loved Justin Jefferson last year, as well, and I’m usually always on the youth in those debates).

I’m really excited about my 2023 projections, and I’ll be writing up division by division Offseason Stealing Signals posts as I go through them. But it’s always important to keep in mind that while projections will give a snapshot of one potential result, the actual NFL season can play out in wildly different ways, and often those extreme outcomes are the biggest hits (and biggest busts) that define fantasy seasons.

Until next time!