Scheme is more important than ever

The young coaches are alright (and are taking over)

“The old world is dying, and the new world struggles to be born. Now is the time of monsters.”

Dan Carlin started his most recent episode of Hardcore History with this quote, attributed to pre-WWII Italian communist Antonio Gramsci. Carlin quickly notes it can apply to a million things, including his episode about Alexander the Great, who lived more than 2,000 years prior to Gramsci.

That second thought about monsters doesn’t apply as clearly to sport as it does to politics and society, but the first sentence gripped me in how it detailed the past half decade of the NFL. As we’ve been talking about this week, defenses changed their approach starting in earnest in 2021, and it immediately made life on offenses more challenging, dramatically shifting leaguewide offensive statistics. That has facilitated an environment of swift change on the offensive side in the years since. It calls to mind that quote about innovation, “necessity is the mother of invention.”

The NFL has always had eras. What I’ve posited about the past five years is the typical evolution of the sport has been sped up drastically, such that we’ve worked through what might have previously been considered multiple different eras. That concept is clearly woven into the QB piece I wrote a couple days ago — consider what I detailed about QB rushing as first an answer to these defensive shifts designed to take away explosive passes with the big rise in 2022, including five 700-yard rushers at the position for the first and only time in NFL history, and that evaporating three years later with none over 600 and just one over 500 rushing yards in 2025.

With any stat like that, as I also covered, there are going to be caveats. In this case, the two best QB rushers from 2024, Lamar Jackson and Jayden Daniels, both missed significant time in 2025. But that doesn’t explain the entire shift. I talked about Jalen Hurts hitting career lows by a significant margin in key rushing stats, and you can even look at a less mobile guy like Daniel Jones, who has always been one of the sneaky mobile types, and see the trend. Jones was one of those 700-yard rushers in 2022, but he totaled just 164 rushing yards in 2025 as he found success in a different way. We’re talking about a guy who averaged 7.1 rush attempts per game from 2022 through 2024 and then in 2025 that number was cut by more than half down to 3.5. In terms of yards per game, he was at 44.3 in 2022 and 12.6 in 2025. And this was in a Colts’ offense that had a QB the year prior in Anthony Richardson who rushed 7.8 times for 45.4 yards per game. They’re different players, but the same coach was there, and there was very similar personnel around them; I hadn’t expected Jones to use his mobility so sparingly in 2025, and yet he did and found success anyway.

Hopefully through that entire QB post, it was clear to the vast majority that I wasn’t trying to actually write off QB mobility as an asset. The subhead “The mobile QB bubble popped” was probably misleading, given I was commenting more on 2025 than what happens next, as I made clear several times in the piece itself. I got some replies on social that suggested reading the title but not the piece, and some confusion about how a bubble popping typically means the value of the item in discussion becoming worthless fairly quickly. That’s obviously not where I stand on QB mobility.

Just to drive home the value I see in QB mobility, before getting to today’s topic, last January I wrote a post based on a fun premise posed to me in a question from a real-life friend, and it’s among the better ways I’ve broken down what athleticism adds to the position. That post was called, “How is Jayden Daniels so good?” and covered how a highly-mobile QB who can also process and make all the downfield throws is a borderline impossible challenge for defenses. Among other things, it also referenced Drake Maye’s massive ceiling as the next man up on that axis, despite his 3-9 rookie season as a starter. Daniels and Maye clearly have different rushing profiles, and the similarity is merely that they can add value with their legs after the stuff they do as passers. But neither is dependent on that mobility, in my estimation.

Anyway, I imagine that was clear to most of you, because that’s been the defining element of the best QBs of this era — Patrick Mahomes, Jackson, and Josh Allen are the past three AP NFL MVPs, and all add mobility to plus passing ability, not as a way to cover for a deficiency. I just didn’t necessarily establish in that piece that the actual ceiling is a QB who does it all.

I also got this question from Adi yesterday I need to add to here:

Thanks Ben. There’s one step in this evolution that I could use some clarity on. I get 11 personnel spread dominance led to defensive adjustments toward lighter / faster personnel which allowed mobile QBs to capitalize on the ground. But as defenses continue to play light, these same QBs are being played off the field or just not rushing as much. Is the logic here that defenses have continued to evolve to the point where they can expose QB processing AND limit their rushing? I understand the Fields’ of the world get played off the field but it feels like there’s more at play even with the mobile QBs who are +’s in processing.

It’s such a good question, and something I’d meant to cover. I’d meant to add that one of the things from The Playcallers was how instead of defenses having to choose this or that, they were coming up with answers that were more this and that. And yeah, I think they’ve probably continued to evolve in exactly that way. Addressing QB scrambles by having spy responsibilities better built into some of the unique coverages and the ways they will sometimes drop linemen and those things — I’m speculating here, but it makes perfect sense in hindsight this type of focus would’ve been the next evolution of what defenses were doing, if this was the thing offenses were going to, and finding success with.

You’re always going to have that chess match, and one of the things I’ve talked about is just because defenses are ahead doesn’t mean they aren’t also iterating. I remember making this point often in 2023, that defenses could continue getting better, because Siegele quoted me back to me a couple times on Stealing Bananas. That was all during a time when people were trying to figure out an offensive counterpunch, but as we’ve learned in the years since, defenses don’t stay stagnant for offenses to figure that out. Offenses have to find answers while defenses try to further tip the scales. There is absolutely a culture in the NFL of always trying to grow.

Anyway, defenses iterating from ahead to stop QB mobility makes perfect sense to me. Right now they have some things working really well on that side of the ball, and it can’t last forever, but they do seem to be finding ways to address additional things.

That makes more sense to me than the alternative explanations. One would be offensive innovation, where teams are finding answers for how to attack specific looks from the defenses, and are basically not asking their QBs to run as much. Another could be rules-based, because as I understand there’s been a bit of an emphasis on QBs needing to slide earlier, and not tiptoe up the sideline before getting out of bounds, which might have led coaches to not want their QBs rushing as much because they are at greater risk. Obviously we also have injuries to key players like Jackson and Daniels, though there are still several instructive examples like Hurts and Jones running less than their own baselines (in similar offenses, because Steichen’s Indy offense has always been similar to what he and they did in Philly, despite obviously evolution in different directions as the years go by), plus the example of Jacoby Brissett and Kyler Murray in the same offense in Arizona. (There’s gray area with everything, but I don’t think, “It’s not actually a trend” is right.)

I did get a reply about offensive performance, and if offensive preference were the main driving factor — i.e. the first alternative I floated above about teams finding different answers — I would think we would be seeing an associated increase in offensive success in other ways, mostly passing. We’re not really seeing that. The comment I got on Twitter referenced TD% rising and INT% remaining stagnant, and argued against the claim there’s a lull in processing for the league’s QBs by claiming there was no data to support it. (That was, to some extent, the side of the argument I was on — I acknowledged there was a temporary lull while more vehemently arguing against what I perceive as an overblown panic about longer-term QB development from people like Tom Brady, so it was funny to hear that for at least one reader, what needed to be commented on what that I’d overstated the lull.)

Anyway, that was a good example of there not being data if you don’t know what you’re looking at, because the commenter ignored QB aDOTs, which is sort of the whole game. He also ignored the new kickoff rules, which we know impacted TD% this year relative to team yardage. More straightforwardly, he ignored that passing and offensive yardage was down in a pretty big way in 2025, because QBs aren’t getting the ball down the field. Taking the shorter passes is going to prevent interceptions — which is a chicken and egg point because if you study this stuff, you know turnover avoidance is a forever trend in terms of offenses always finding ways to prioritize ball control, which is why they aren’t pushing downfield — and the kickoff rules might help TD%, but everything else tells the story I’m detailing.

Anyway, the data does support passing games still struggling in these ways, and then to also lose QB rushing suggests to me that defenses are iterating and getting better at handling this and that, and pulling the plug there, as well. As far as raw yardage, losing QB rushing in addition to passing continuing to decline meant offensive production was down by more than 10 yards per team game from 2024, which made it the lowest yardage-per-game season in the NFL since 2007.

I’ll get into more about that in the next post, when I do finally get to the diluted list of ways 2025 was a transformative NFL season. I promised it by the end of January, and I failed, as I keep branching topics off on their own instead (after several hours of writing yesterday, I decided that was an arbitrary deadline, and I should probably look things over with fresh eyes today).

The below, which the title and subtitles of this post reference, was really meant to be two more parts of the themes countdown. First, NFL coaching is getting younger. Second, NFL coaching is getting better, and with defenses taking away so much, good schemes as a way to create much-needed explosive plays are so, so impactful.

Here’s what I put together on those topics.

The young coaches are alright (and taking over)

Innovation in the sport is typically driven by offenses, largely because they are the ones with the ball trying to execute a specific, designed vision. Defenses are reacting; their object is to prevent something from occurring, though it’s unknown to them how the offense will try to achieve that goal.

If the offense’s method becomes known to the defense in any way that the offense picks up on, the offense is going to change what they are doing. The offense is trying to deceive; misdirection is at the root of most great offensive plays and schemes, from macro stuff like marrying run and pass concepts to micro elements like motion and blocking tells on specific plays.

But it’s been defensive innovation that has been responsible for much of the recent evolution of the sport, and that has really shaken things up. One of main ways I’ve understood it and then discussed it back with you guys is to reference how defenses are more willing in this era to dictate their own goals, as opposed to that concept of reacting to what the offense is doing. And when both sides are dictating, the chess match heats up, like two boxers on the offensive getting into a slugfest.

And one of the results has been teams leaning into youth for fresh, new ideas. I’ve talked about coaching age before, and have always tied it back to a 2012 book that was well ahead of its time, from Frank DuPont (aka the Fantasy Douche) titled, Game Plan: A radical approach to decision making in the NFL. I used to work for Frank, and consider him something of a mentor, but I’ve never actually shared stuff from that book because I’m not sure if there’s a digital copy. (Despite being an amazing read, I don’t think it was exactly a best-seller.) But I want to reference some charts he made, so I’m going to go ahead and take pictures of pages. Hopefully that’s cool. Here are a few of the charts and points that stuck with me most. (You can buy the paperback of this book on Amazon for $5.99.)

Very early in the book, Frank establishes that many of the world’s “geniuses” throughout human history were quite young, like in their 20s, when they reached the pinnacles of their vocations (from older philosophers, physicists, and composers, to more modern musicians and artists). An analogy Frank draws on heavily as the book moves on is the poker boom in the aughts, and how younger players took over even the live events in part because of a new world where they could rapidly gain experience through the nature of online poker and increased rate of simulations over time.

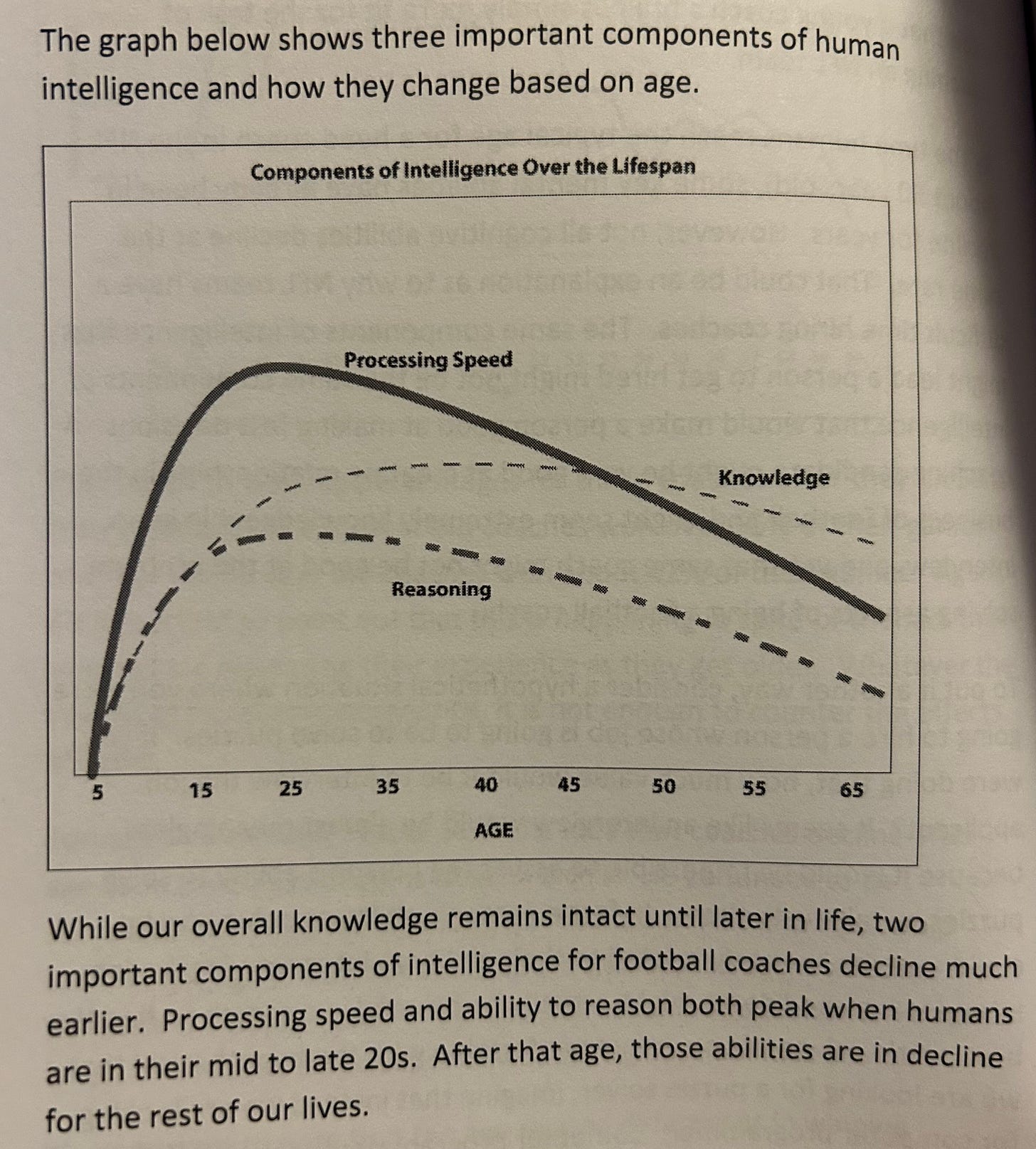

Frank goes on to talk about the Madden generation, a concept he attributes to Bill Simmons, which talks similarly about younger people in the football world having had increased access to simulations and reps via video games that probably help with elements like game management decisions even versus actual coaches who have been doing it for decades. This is again attributed to this idea of simulations and feedback loops. Older coaches really only get something like 16 points of feedback a year from their own games, similar to the old wave of brick-and-mortar poker greats having played for decades but being quickly surpassed in total hands played by people far younger, something Frank shows with math as he estimates the speed it takes to play a hand online versus in person, plus the way internet poker allows for multi-tabling, and also doesn’t require commute time or anything of that nature, so there’s an exponential rate of hands that can be played in a day/month/year/decade. (All of this is written way better in the book, and you should just buy and read it, but a key point is if you are learning way more rapidly, you can gain far more experience while your processing speed and reasoning are still at their peak, as described by the visual above.)

Football isn’t exactly the same, but Frank does a good job of detailing how it’s not massively different. You need to think about a lot of things at once, including being able to self-analyze for tells. You are under constant time pressure, both in a week while gameplanning and installing, and especially during a game when the clock does not give you a lot of time to think.

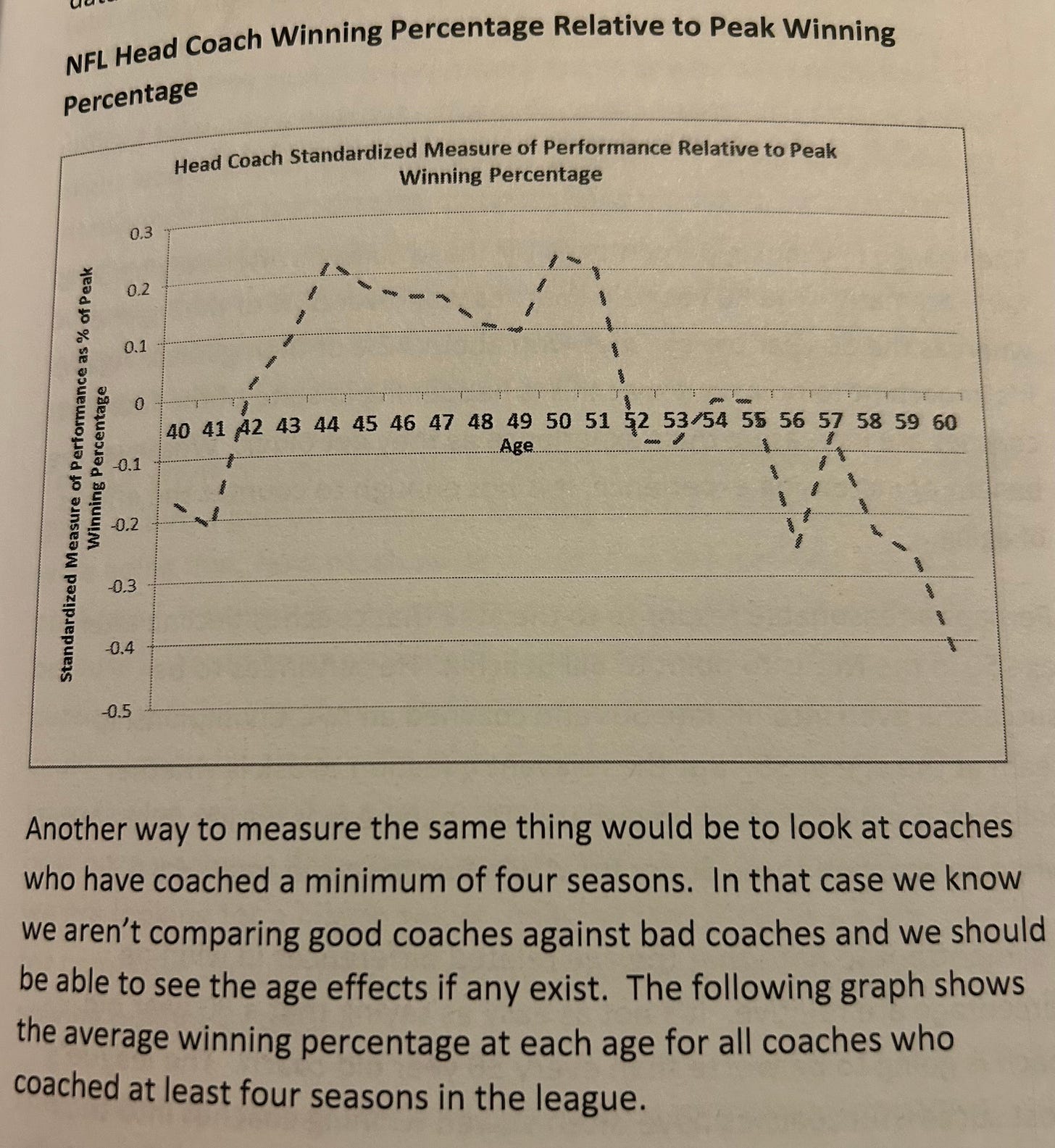

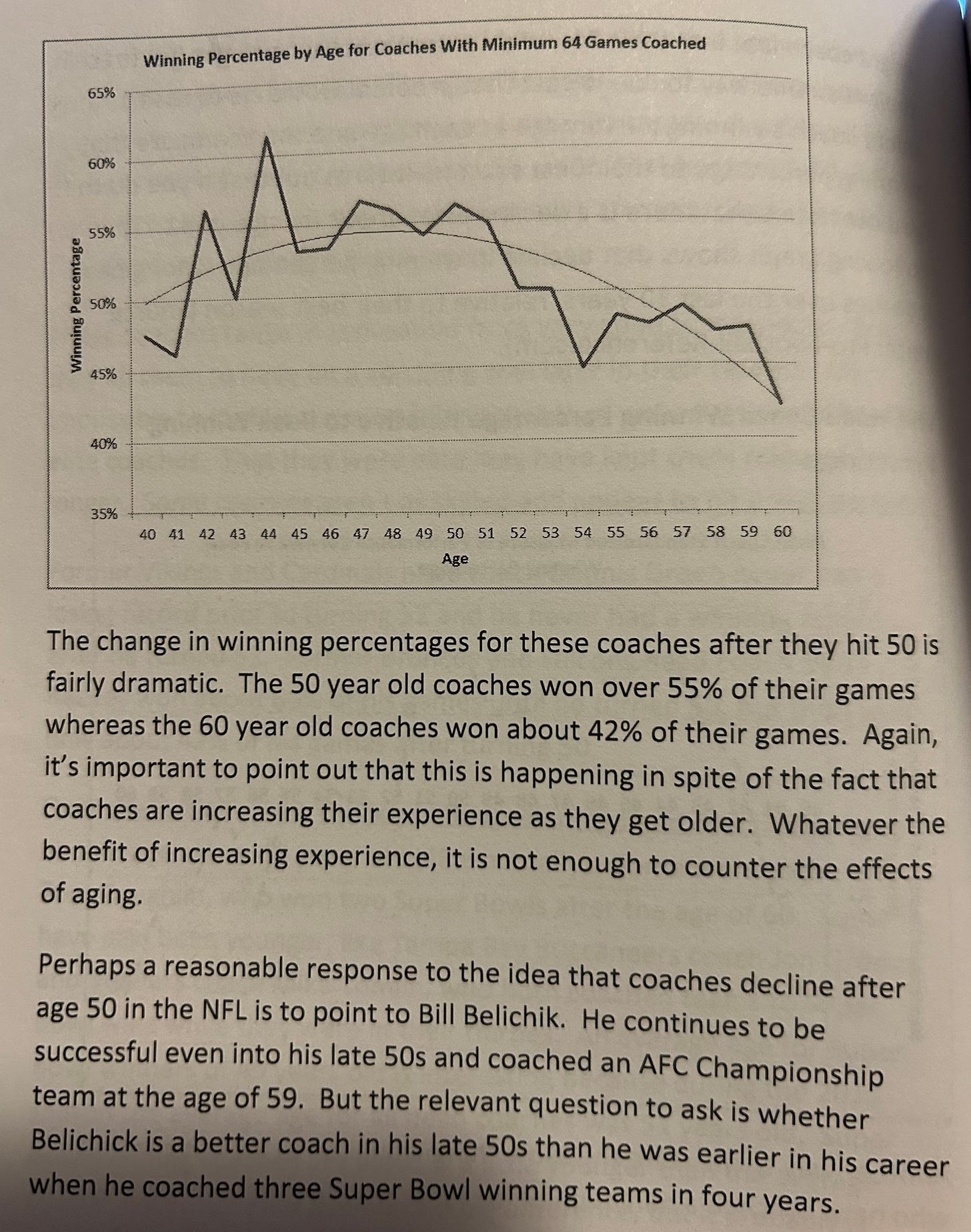

And then Frank hits us with some NFL data, and keep in mind this is from 2012, so we’re talking about this coming from well before Sean McVay was hired in 2017 as the league’s youngest ever head coach at the time, at 31. When Frank wrote this, it was extremely ahead of its time; his charts also just didn’t have a ton of young coach data, and they would look a lot different now. But young head coaches have found a lot of success in recent years; I wouldn’t worry so much about that side as much as the decline on the back end, which is something observed before 2012 with a large enough sample that we can be confident it still holds.

I left that last note about Belichick in there, because of what we now know about the tail end of his Patriots’ career, and what’s happened at UNC, as well as the recent revelation he was snubbed as a first-ballot Hall of Famer. I still think Belichick is far and away the best head coach of all time, and I really don’t care about how he did after Tom Brady left, because by the time Brady signed with the Bucs, Belichick was within a month of his 68th birthday. (If you saw me recently argue on social how silly the Belichick with and without Brady splits are, that’s part of why. The prime of Belichick’s coaching career was when he was younger, in the earlier part of Brady’s career. People who say “Brady carried Belichick” can’t see how that evolved over time, and maybe that was more true on the back end, but it was probably more reversed on the front end of a very long partnership that was obviously symbiotic.)

Moving on, though, we can look at the current landscape, and we got some massive first-time head coach successes in 2025, including Ben Johnson, Liam Coen, and Kellen Moore. That followed the Seahawks’ home-run hire the year before of Mike Macdonald; of those four, Coen turning 40 back in November makes him the elder statesman.

One of the reasons I’m so high on Macdonald is he notably feuded with his offensive coordinator in his first year, then made an extremely aggressive move to quickly move on from him after one season. I’ve argued that if you move onto a second coordinator that quickly and it doesn’t work, you’re shortening your own leash, because we know coaches don’t get unlimited chances. But Macdonald understood the assignment, and made his own home-run hire with Klint Kubiak, and the team’s schematic direction is I think a massive reason they are in the Super Bowl.

What Frank wrote about in 2012 has finally become undeniable to the degree that a league famously tied to retreads and protected members of the inner circle appears to be shifting en masse. Guys like Mike McCarthy still landed jobs, but we heard about interviews for guys like Arthur Smith and Matt Nagy and those guys did not land jobs (Nagy still might, but it’s looking more like the Chiefs just moved on from him and whatever role he takes next will be a demotion).

Meanwhile, the sheer number of young coaches who got hired to coordinator positions has shocked me. I frankly thought that after guys like Johnson, Coen, and Moore got bigger opportunities last year, the league’s well of hot, young coaches probably needed an offseason or two to catch up. That 2026 was going to be a down cycle in that regard.

But the league didn’t care. There can’t possibly be a never-ending stream of revolutionary young minds, but the league just started hiring guys to coordinator positions that have been coaching for only a year or two. Show some promise, we’ll promote you rapidly. I’m sure there are a ton of middle-aged coaches who are pretty pissed they just got passed over as this switch flipped.

Among head coaches, we did get a lot of older guys and CEO types, though Joe Brady got the Bills’ job at 36, Jesse Minter got the Ravens’ job at 42, and it sounds like 38-year-old Kubiak is in line for the Raiders’ job. Meanwhile, Rams’ passing game coordinator Nate Scheelhaase got interviews at 35, Broncos’ QB coach Davis Webb was discussed at 31, and Jaguars’ OC Grant Udinksi got some looks at 30, among others. The Cardinals are the last team to figure out a head coach, and it’s possible that role will also wind up going to a younger guy, though the reported finalists do appear to be older options.

But the point this offseason is more about coordinators, including a couple who were backup QBs in the NFL just a couple years ago. Look at this list of under-40 coordinator hires:

Declan Doyle, Ravens OC (29)

David Blough, Commanders OC (30)

Davis Webb, promoted to Broncos OC (31)

Sean Mannion, Eagles OC (33)

Tommy Rees, Falcons OC (33)

Christian Parker, Cowboys DC (34)

Chris O’Leary, Chargers DC (34)

Brian Duker, Jets DC (36)

Drew Petzing, Lions OC (38)

Zac Robinson, Bucs OC (39)

Those last two guys latched on in new cities after coordinating elsewhere last year; some of those top names are super young. There are also several in their forties, which is the low side of the charts Frank made 14 years ago, including Mike McDaniel landing the Chargers’ OC gig at what seems like a very well-polished 42 years old, and two new DCs that are 43, the Bills’ Jim Leonhard and the Giants’ Dennard Wilson.

Coordinators do tend to run younger, but there are still openings available, and if we don’t have a longer list of currently employed under-40 coordinators in the NFL right now than ever before, that would shock me. I’m not sure exactly how to look that up, to be honest, but my guess is it’s not close. There have always been more uninspiring names that boast experience with limited results who land these jobs, like the Arthur Smiths of the world, but that well just dried up in a hurry this cycle. Again, I’d bet a lot of middle-aged coaches are talking to their agents this month, feeling like they got passed over and boxed out by a big macro switch that flipped.

Anyway, I wanted to start by establishing the point about younger coaches from Frank’s book, and talk about what we’ve seen just this month with the hiring cycle slowing down and landing on a bunch of new names. But the reasons we’re seeing this are all about what we saw on the field in 2025. Macdonald, Johnson, Coen, and Moore all overperformed even lofty expectations as recently-hired head coaches, and they did so because of a shared ability to put players in the best position to succeed.