This is a weird week. As I write this, I have not seen basically 4.5 games from yesterday, which certainly makes it hard to write any kind of sweeping intro about what Week 5 meant. And obviously, Monday Night Football will be played, so I have a lot of football-watching to do later, which I usually don’t on Mondays.

But 3.5 of those games from yesterday will be covered in Part 2, so I’ll just work through the one game for today in a little bit, then I’ll watch this evening and get ready for tomorrow’s writeup.

The reason for all that is I got the chance to go to two playoff baseball games on Saturday and Sunday, and man, what an experience. In advance of that, I did some prewriting of the Thursday game on Friday morning, and I do have a football-related intro for you from that.

But then I also got a lot of feedback on my recent Mariners-related intro, so after I talk some football here in the intro, I’m going to do a second intro and talk a bit of baseball. For those of you who don’t love that, obviously skip ahead to the games. But please let me warn you for the games, as well, I’m not sure anything I wrote made any sense this week. I’m in a weird headspace for this.

My football notes from TNF were about the new overtime rules, and specifically the strategy when you win the coin toss about whether to take the ball first or voluntarily elect to kick off. That strategy has been fun to watch play out in recent weeks, and we have three interesting outcomes that kind of run the gamut of what to think about (caveat there’s a possibility there were more overtime games from Week 5 I haven’t seen yet).

On Thursday Night Football, the Rams lost after going for it on fourth-and-1 from the 11-yard line, down 3 after the 49ers made a field goal on the opening possession of overtime. I support the “go” decision there, particularly with 3:41 left in overtime, where a field goal to tie the game quite possibly means never seeing the ball again, with your two most likely outcomes being either a tie or a loss. Going for it, and with just the one yard to go, is proactively trying to win the game. That’s pretty straightforward.

But it also begs the question of whether having the ball second in overtime is actually preferred? The Rams won the toss and chose to kick, which is what the Packers did in Week 4 against the Cowboys, and Green Bay very nearly ran out of time on their possession. In digging around for the logic here, I found an ESPN article from before Week 4 that was building off the Cowboys’ overtime win over the Giants back in Week 2, where Ben Solak and Seth Walder interviewed analytics staffers and dug into what the right decision is. They largely landed on the idea that it’s fairly evenly split, and that their models support that.

But all three teams in the past few weeks have elected to kick, based on the logic that they’d prefer to know what their opponent did before having their own chance with the ball. As Solak and Walder discuss, that reasoning is undoubtedly impacted by the outcome of the Chiefs-49ers Super Bowl a couple years ago, where San Francisco made a field goal on the first drive and then Kansas City drove down and walked it off with a touchdown.

The Rams were in the same position against San Francisco on Thursday night, but failed to accomplish the same result. And one of the fascinating things that came up was this difference between the regular season and the postseason, where there can’t be a second overtime. In the Chiefs’ Super Bowl win, they scored on the final play of the first overtime, but they were never really in hurry-up mode, because in the playoffs, there would have just been a normal quarter break and the game would have moved to second overtime. In the playoffs, the first overtime was also a 15-minute period, rather than a 10-minute period we get in the regular season. And yet, that Chiefs-49ers’ game took up the whole 15-minute period with just the two possessions.

A huge part of this discussion for me comes down to how teams actually score these days, which is often the whole matriculate the ball downfield thing, which takes time. We’re seeing fewer overall possessions in games, and if the calculation for what to do comes down to thinking through scenarios where the first team scores and then the second team wants to know what that information is, well those scoring drives are going to feature multiple first downs, and typically a lot of plays. We’re more likely to run into the constraint at the end of the first overtime that says that in the regular season, that’s it. The game won’t go on no matter what.

That’s what almost cost the Packers in Week 4. With only a 10-minute overtime period and no possibility for a second overtime, this note about how the Super Bowl data point everyone is responding to featured two long possessions that wiped a whole 15-minute period helps explain how the Packers ran out of time. The Cowboys drove down and got their field goal in 5:20 of game time, meaning the Packers took over with 4:40 remaining, including a 2-minute stoppage. That’s enough time if you’re hurrying, but it’s a long drive to get into touchdown-scoring range, and you can’t just dictate when you convert and those things.

Now, the chief benefit of knowing what you need on the second possession is how you can extend that drives, and the Packers took full advantage of that. To convert their initial first down of the drive, it took Green Bay all four downs, and certainly if they had possessed the ball first it would have been difficult to justify going for it on fourth down deep in their own territory if they didn’t already know the Cowboys had scored on their drive and that was the game. And Green Bay did convert that fourth down.

Those four downs just to get the initial first down also helped contribute to what became a 13-play drive, where time wound up being a major factor. Ultimately, Green Bay was in a position with a running clock late, where things got really low, and an incompletion to the end zone left just one second for them to kick a field goal for the tie. That field goal came on a fourth-and-14, but part of why I say they ran out of time was the third down play was rushed and needed to be to the end zone. If they had unlimited time, quite possibly their third-down play would have been to try to set up a fourth-and-manageable for a potential “go” decision so they weren’t just settling for a tie game.

And all that happened despite Dallas only getting a field goal, which is to say that if the Cowboys had actually scored a touchdown on the first drive, they likely would have taken even more time, further pressuring Green Bay on the way back. So on one hand, you might run out of time, but then what we saw on Thursday night of Week 4 was how there’s also this issue with the third possession. In the playoffs, the third possession element is discussed in scenarios where both teams have the same outcome on their first possessions, and it’s talked about from the perspective that then the team who had ball first also gets that first shot to on a do-or-die possession with the third possession in overtime. Part of that discussion is the second team knows that, so they can do a couple things, including going for it rather than kick a field goal to match the first team’s field goal, like the situation the Rams were in on TNF, or if they match a touchdown, they can go for a 2-point conversion to decide the game there, rather than kick an extra point and hand over that third possession advantage voluntarily.

However, the Rams went for it in that spot in large part because they got themselves into a fourth-and-1, and not every situation is going to play out that way. If Los Angeles were at something like fourth-and-10 in field goal range, it might be the case that they would actually want to just take the field goal. Or, put differently, going for it in that spot would be low probability enough that there was actually an advantage for the first team to just kicking a field goal and not having to make that decision. The second team has to decide whether to play for a tie or be the one who tries to convert a difficult fourth down, whereas the first team just kicks the field goal because they don’t know any better. There are obviously gradients here, but I find the game theory fascinating.

Going down this rabbit hole I’m down a little bit further, specifically this decision about kicking a field goal with the second possession, when you find yourself in that situation under the playoff overtime rules, you can think through getting the ball back on the fourth possession. So, in the hypothetical the Rams were in a similar situation to TNF but had fourth-and-10 or fourth-and-15 or something, under playoff rules they could kick to tie the game, and they would still be deciding to give the ball back to San Francisco with a do-or-die shot on the third possession of OT, but because playoff games can’t end in a tie, they could essentially play for a stop on that next drive and then they’d get their chance to win on the fourth possession (their second possession, but fourth combined) of overtime.

But in the regular season, this constraint of only one 10-minute overtime period means that in all likelihood a fourth possession will never occur. I just got done talking about the Packers not even getting through the second possession, and then certainly it played into the Rams’ calculation — and more specifically would have if they had a tougher “go” decision where it wasn’t fourth-and-1 but maybe like fourth-and-5 — that there was 3:41 left in overtime, which was enough time for San Francisco to win it, and also potentially just the right amount of time for the Rams to not get another chance, even if the 49ers didn’t win it.

But that’s where we get into our third recent data point, which adds a fascinating layer to this discussion. There were actually five combined possessions in the 10-minute period that decided the Cowboys-Giants overtime game in Week 2. With both teams punting rather quickly, there was enough time for the Cowboys to need to punt a second time, and then Russell Wilson threw a pick on just the second play of the Giants’ second chance, which gave the Cowboys a third possession, and the fifth one overall. So again, there are shades of gray here, and these things aren’t perfect by any means. But one note here is even in this outcome, the Cowboys were at an advantage by going first — they won that game in part because they got three possessions in that overtime period and the Giants got two. The calculations all come down to an assumption that both teams are going to score in some fashion on their first possession, but when you run into the scenarios where neither team scores, you’d very obviously like to be the team who had ball first because then you get to try a second time first, and then potentially even a third time.

And that part of it does relate back to the field goal situations, as well. Really, going second is an advantage because you know you will need to go for it on fourth down, but in the outcomes where at least one team kicks a field goal, there’s kind of a slight advantage, with the 10-minute, single-period constraint, of being the first team that has to make that decision. This isn’t like college football where if you also settle for a field goal on your possession, we all just do it again in double overtime.

So this element where two field goals, or potentially also two punts, could equate to exactly three possessions in the overtime period and no more, is something that should be considered. On a long enough timeline, there will presumably be outcomes where the team who starts first gets that third possession, fails to score, and then the game ends in a tie where the team who got the ball second only got one chance to score, but the team who got the ball first got two.

Again, in the playoffs, that third possession element is thought of as an advantage because you get ball first in what is now sudden death, but where that sudden death will continue forever. In the regular season, it might be that the time constraint can hit you on your second possession — like it did the Packers — or after your opponent gets the third possession, and in either case by going second you are being pretty significantly impacted by the “10 minutes and no more” element in the regular season.

And what really drives this home is the key discussion here is when both teams are putting together scoring drives, because in the modern NFL the scoring drives typically take up five minutes or so. As we just talked about, if both teams punt quick like in Cowboys-Giants, you just want to go first because you get ball again on that third possession. So the only justification for opting to kick is in these scenarios where the teams both move the ball, which are overwhelmingly the scenarios where clock has been run and the 10 minutes becomes an issue.

Now, the models are obviously picking up on all these things, and I trust when they say it’s basically a toss-up because of the advantages you do still get by going second, namely the Packers’ example of going for it on fourth down deep in their own territory, and then also that ability to go for a 2-point conversion when both teams score a touchdown. But I find it pretty interesting that the analytics staffers interviewed in the ESPN piece essentially admitted to being influenced by the past Super Bowl result, when the parameters of playoff overtime are so much different. The lack of a one-overtime constraint is massive in this discussion, as I’ve broken down. It significantly alters the game theory equation, such that what happened between the 49ers and Chiefs almost shouldn’t be relevant to the decisions these teams are making for regular season overtime games.

And another thing about how these teams are deciding on this is that the models are inherently going to consider averages, like average drive length and those things. I’m not trying to say the models can’t be dialed into the specifics of a given matchup, but just that inherently they have to be based on inputs. But the thing that I actually think is probably right is to try to actively take a strategy that would manipulate those inputs.

What I think teams should do is take ball first, and then put together the longest, slowest drive they can. Force the other team to potentially be burning timeouts on defense before you’re done with it. Even if you settle for a field goal, if you do that in eight minutes where your opponent burned their two timeouts, you’ve now made them one-dimensional on offense. They have to throw, and they have to try to get out of bounds and all that. You can feel good about preventing them from getting the touchdown drive coming back that is the whole benefit of going second, and maybe even preventing the field goal to tie. Or, obviously, if you spend eight minutes and score a TD, that’s it.

My understanding, by the way, and I don’t have this confirmed but I was trying to figure it out, is that if you can use up all 10 minutes — which includes the 2-minute stoppage and also your opponent having two timeouts — both teams don’t actually get a chance to possess the ball. (For what it’s worth, on the NFL’s official page for this, they don’t clarify, stating both that “no more than one 10-minute overtime” will be played and also “each team must have an opportunity to possess the ball” with the only exception listed being the team who kicks off recording a safety, where they would win without possessing the ball. There’s a very obvious question of, “What happens if one team possesses the ball for the whole 10 minutes?” that is not addressed, but again, from what I can gather the 10-minute rule overrules the “both teams get possession” rule, which is similar to why the Packers didn’t get to finish their drive on their own time.)

So anyway, the models are accounting for various factors, but the goal would be to operate so slowly that you’re changing the math of the model because you’re asking it to account for a first possession that — when successful, and even if that’s just a first down or two — runs a good chunk of clock. And obviously NFL teams sometimes need to use tempo for efficiency reasons, and you can’t just run a ton of clock and also ensure offensive success. That’s not how this works.

But if you’re trying to run clock, you’re likely to create different outcomes that are advantageous to having ball first. If you do drive down and score, and even in a field goal situation as I talked about above, you can make time a constraint like it became for the Packers on their second drive. Even if you don’t drive down and score, like you move the ball a bit but take a couple unfortunate penalties that knock you out of long field goal range and you really can’t afford to go for it because you need 20 yards or something, using up a lot of clock will turn the ball over in a situation where if you do get the stop you’ll obviously need, you’ve also essentially ensured this will be a three-possession overtime where you’ll get the ball back with like two minutes remaining and you’ll get to control things and have it last, so that if you don’t succeed again the second time, you just end in a tie with your opponent only getting the one opportunity.

I think if you take ball first, and you’re really trying to be methodical about running the play clock down and milking time, while also obviously trying to get down in scoring range, the variety of outcomes does probably lean your way. And the big thing here is you’re in control of that when you have the ball. When you give away first possession, your opponent can dictate the pace of the period, and how many possessions might be possible.

Obviously all of these discussions assume execution, but I’d like to point out that the whole idea of giving away first possession also assumes execution — i.e. both teams scoring on their opening drives — as I’ve talked about. Again, there’s no world where if neither team scores you’d prefer to go second.

So anyway, while going second has been a benefit in a couple of spots, including the Packers knowing they needed to convert that early fourth down in their own territory, it’s also pretty clearly run into some issues at the end, including in a situation similar to Thursday night. Had the Rams needed more yardage to gain, they would have had to make a decision about kicking a field goal to tie with just enough time left for their opponent to possibly have final possession.

It’s all a very fascinating discussion to think through. I’m not confident I have it all sorted, and know better than the models. But I do think I know how I’d try to coach it up and play it. And that’s doing the opposite of what seems to be the conventional wisdom right now. Give me the ball.

Alright, that was longer than expected, so I’ll try to talk Mariners quickly. As I said, if you’re not a baseball person, definitely skip ahead to the football games, starting with the Rams-49ers below. There isn’t anything but baseball talk between here and there.

Saturday night’s game was an insane atmosphere, and the M’s went ahead on a Julio Rodriguez home run, and then fell behind 2-1 when the Tigers got a two-run home run, and then the stars Cal Raleigh and Julio had huge hits in the bottom of the sixth to tie it back up 2-2. But after what I felt was a pretty major baserunning error from Julio — who for a superstar that has incredible defensive instincts, somehow the baserunning doesn’t really come intuitively for him — where he ran into a tag as the trail runner with no outs on a ground ball to the second baseman that allowed for a double play when he should have been doing whatever he could to shut it down, or just slide way too early, or anything to better avoid the tag to allow the batter to get to first, and then Raleigh, who was on second, could have gotten over to third with one out, and he’s the go-ahead run and now you have a sac fly situation.

Anyway, you certainly don’t put a whole game on one play, and you certainly wouldn’t blame the guy who homered and later drove in the team’s only other run, but it was just an unfortunate situation where a double play there is the major thing to avoid at all costs when you have two on and no outs, and the play was in front of Julio and I understand trying to beat the play and that everything is easier said than done, but it’s one I think he’d probably like to have back. And it just got compounded by the M’s then not threatening in any other inning after that 6th inning, all the way through the 11th, where they lost thanks to a walk, wild pitch, and seeing-eye single.

But the vibes were crazy all game. At least until they weren’t, and then last night, it was a whole different thing. I mean, the vibes were still awesome, but you could feel the tension. And Saturday was rough. The inning breaks are a lot longer than the regular season given it’s the postseason and commercials and all that, and losing in 11 innings took it out of me. I was going Sunday with Stealing Signals subscriber Andrew, who reached out a couple weeks ago after I wrote about the M’s here, to mention he had a line on some tickets and invite me to a game.

But going Sunday was rough after Saturday. One of the things about the Mariners is how thin the roster has been for so many years, and how it’s actually pretty deep this year, but that’s what made Game 1 so rough. The two superstars Cal Raleigh and Julio Rodriguez both showed up with 3-for-5 nights to combine for 6 hits, and then the rest of the lineup combined for… zero. And that was the whole thing we had addressed. That was the thing that couldn’t happen.

But if we were going to go out and beat a Cy Young winner in Tarik Skubal in Game 2, someone else had to step up. And Jorge Polanco had one of the very best position player performances I’ve ever seen live. Polanco’s a veteran who we’ve DH’d most of the year, but as we added so bats at the deadline and got healthier, and our other 2B options have struggled, we started playing him at 2B a lot more to get more bats in the lineup. And yet this dude made two defensive plays that were exceptional if he was a young, glove-first middle infielder, smothering an absolute rocket hit right at him with insane top spin for an in-between hop he couldn’t short- or long-hop, and then later making a backhand play on a ball up the middle I thought he had no shot to reach, with a runner on first that surely would’ve gotten to third, and not just keeping the ball in the infield but quickly underhand flipping to get the lead runner at second. I mean, he did it so quick our SS J.P. Crawford gave the throw over to first because it was like, “Shit, maybe we can get a double play?” which we definitely didn’t but Polanco’s jump from deep in the hole against a lefty, then smoothly gloving that and flipping it so quickly, it was just a massive out.

But offensively, facing Skubal, who in the stands we were just openly hoping to get his pitch count up because this guy was not going to be beaten, Polanco got into one for a solo home run in his second at bat, in the fourth inning. And then when he came up for the third time, Skubal was still in, and all the other Mariners had combined for two hits at that point, and Polanco got his second hit off Skubal, and it again wasn’t just a hit but one of those ones that clears the wall and you get to go all the way around the bases. And I mean to have two hits off an ace who at that point had given up two total to the whole rest of the team, and your two are both home runs, is just absurd. I’ve seen more offensive production, but given the context of this low-scoring playoff game where your team absolutely has to have this game and you’re facing a superstar, I don’t know that I’ve ever seen a more impressive day, as I said. It was incredible.

And so the tension that was there in the crowd at the start of the game, when the Mariners went up 1-0 in the fourth and then 2-0 in the sixth, it had turned. The middle innings were a party again, like Saturday. And then in the top of the eighth, Matt Brash did Matt Brash things and walked the leadoff hitter and then eventually missed over the middle of the plate for a game-tying, 2-run double, because he’s apparently a late-inning, high-leverage reliever but he has no command and misses his spots both off the plate and over the middle, which equates to the unholy combination of free passes and hard contact, which as far as I’m concerned should be disqualifying for a high-leverage reliever no matter how high your whiff rate is because you do have nasty stuff when you locate, but I’m not in charge of these decisions. (In Brash’s defense, he did get a ground ball that went for an error. In first baseman Josh Naylor’s defense, the error he committed was on a rocket, and it’s one of those things where obviously you want the guy to make the play, but also you’re just not going to get perfect defense if you’re getting hit hard.)

And things got tense again. We had the top of the order, but Seattle fans, for how amazing they are, are a beaten-down group. Randy Arozarena struck out. Cal Raleigh came up with one out and no one on, and he was 0-for-3 on the night. The stadium started a noise prompt for the crowd to chant “M-V-P” for Cal, which has rung through that stadium for weeks, every time this dude has been up, both games when he’s walked out to the bullpen to warm up the starting pitcher, basically every time he’s left the dugout. But the chant was weak. I thought everyone was going to stand up, and I did stand up and start chanting a little, thinking it would build, and I mean I literally said out loud, “OK, I guess we’re not doing that” and sat back down because no one was up and I was in the second row and you don’t wan to be that one guy blocking the view of everyone behind you. The atmosphere shift was insane.

And there’s just zero way, absolutely no way Cal didn’t feel that. Like I said, he’s been hearing thunderous MVP chants every AB for weeks. But there was almost a resignation, a smattering of optimistic fans drowned out by what was just palpable anxiety. And I just don’t know how you don’t feel the pressure there. I just don’t know how you rip the first pitch down the right line for a double when there are 50,000 people suddenly not steadfastly believing you can walk on water. And you know yourself that your teammates are mostly struggling, and if you don’t meet this moment in the eighth inning, there are two outs and no one on and unless someone runs into a solo home run, there’s a real chance not only are we not scoring in the 8th, but we’re maybe not scoring for a few innings again and it’s “hopefully we win in 11” all over again.

I mean as far as MVP moments go, not that this has anything to do with the award, but to stand up there in the moment, and to come up huge in that moment, is almost unbelievable. It was the hardest-hit ball of the night by either team in terms of exit velocity, at 110.9. And yet, it wasn’t enough to overcome the anxiety of the crowd. I mean, people were fired up, but Cal has hit 60 home runs this year, and you could almost sense this feeling that a double maybe wasn’t quite good enough. We needed a run on the board, and Cal was our hope to do that with one swing.

And then Julio steps up, takes a ball, and then rips the 1-0 pitch down the left field line for his own double, a mirror image of Cal’s. And the place went absolutely batshit. You can’t have highs without lows, and all of that. Saturday was brutal. Getting a lead on Skubal and then blowing it in the eighth, and feeling like it was happening again, and if you start 0-2 at home your season is just done. The anxiety I just described in the crowd wasn’t for no reason. For the two superstars, on three pitches, to come up massive in that moment, was just the coolest goddamn thing I’ve ever seen.

And then our closer, who worked two scoreless innings Saturday, came in and struck out the first batter on three pitches, then got ahead 0-1 on the second batter before getting a pop up, and then finally threw his first ball to the third hitter he faced, and went down 2-0 but didn’t give in, throwing back-to-back sliders for strikes to get back even at 2-2, and then induced three more foul balls before giving up the third ball, and then got the groundout to seal the game out of the full count. If you want to talk about a reliever who does have the command to work high-leverage innings, let’s talk about Andres Munoz, who again got six outs the night before but looked like he could’ve gotten nine last night without really breaking too much of a sweat.

To Detroit for Games 3 and 4 on Tuesday and Wednesday. If it comes back to Seattle for Game 5 on Friday, you know I’ll be there.

Let’s get to the games. You can always find an audio version of the posts in the Substack app, and people seem to really like that. You can also find easier-to-see versions of the visuals at the main site, bengretch.substack.com.

Data is typically courtesy of NFL fastR via the awesome Jay (follow Jay on Twitter at FFCoder or check out his Daily Dynasties site), but I will also pull from RotoViz apps, Pro Football Reference, PFF, NFL Pro, Next Gen Stats, Fantasy Life, and the Fantasy Points Data Suite. Part 1 of Week 1 had a glossary of key terms to know.

49ers 26, Rams 23

Key Stat: 49ers — 82 plays, 49 pass attempts (both led Week 5, through Sunday)

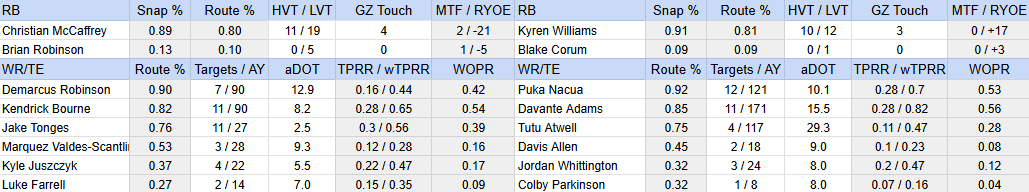

Week 5 opened with a fascinating divisional game as Kyle Shanahan and Sean McVay — often considered co-architects of the modern offensive wave across the NFL with a substantial number of their assistants hired as head coaches installing similar systems in various cities — met for the 19th time in the regular season. Shanahan had the head-to-head advantage for a long time, but McVay won their Conference Championship matchup in January, 2022, and McVay had also won three of the past four regular season matchups heading into Thursday night, where the Rams were favored by more than a touchdown. Shanahan still held the lifetime edge 11-7, and he moved to 12-7 despite being a big road underdog on a short week with several significant injuries. And as probably expected, for as well as San Francisco played, it could be said the Rams gave this one away. That’s just sort of how a lot of games are decided these days, and the 49ers deserve a ton of credit as underdogs for possessing the ball, building an early lead, and doing a good job of keeping the Rams off the field and shortening the game. But the Rams missed a field goal early in the second half down 10, then had an extra point blocked after tying the game, when it could have given them a 1-point lead, then after a San Francisco field goal made it a 3-point margin again, they were going for a touchdown with about a minute left, which led to a compounded error of Kyren Williams (14-65, 10-8-66-2) fumbling inside the 5-yard line. Obviously, he needs to not fumble there, and it’s always the case that things wouldn’t have played out exactly the same because the events between the missed extra point and the fumble were impacted by the score being tied rather than a 1-point game (for example, the Rams had a three-and-out on their one possession in the interim, and threw all three downs, which they probably did because they were tied but may not have if they were up 1), but there’s also this scenario where with a made extra point the Rams are in a similar spot late and are only down 2 (after a San Francisco field goal), at which point they aren’t even trying to score a TD necessarily, versus running the clock down for a field goal try even shorter than an extra point. The 49ers had used two timeouts in the third quarter — even before the blocked extra point — and Kyren’s fumble came on first down, so if the Rams were in a similar situation but where a field goal would win, they would’ve been able to control the clock all the way down to a walk-off chip shot. A whole lot of hypotheticals there, obviously, but it’s an interesting case study in how one mistake can lead to other risk, and then often other mistakes. Ultimately, the Rams did force the 49ers to punt from deep in their own territory and get the ball back in time to kick a (longer) game-tying field goal and force overtime, which I wrote about in the introduction. They lost in overtime after the 49ers kicked another field goal on the first drive and the Rams couldn’t get the one yard they needed on fourth-and-1.

Christian McCaffrey (22-57, 9-8-82-1) was the centerpiece on offense for San Francisco, as expected. His TD came on a slot route where there was a linebacker over him and he just ran an out route and obviously one of the very best slot WRs in the NFL is going to create separation on a linebacker in that spot. I haven’t maybe harped on RB air yards as much as I should have this year, but it’s long been a favorite topic of Stealing Signals, and it’s becoming a bigger trend that will need to be an introduction soon. But because RBs typically get a lot of passes around the line of scrimmage, it’s not uncommon for them to be very near to zero air yards for the whole season, or even in the negative, meaning their average target came behind the line of scrimmage. When I’ve talked about RB air yards, I’ve talked about how getting vertical usage isn’t typically going to be consistent for a RB, but that simply the presence of it is Signal from the perspective that it creates additional weekly upside paths for those RBs to score. When I say it isn’t going to be consistent, what I mean is that per RotoViz, Ty Johnson led all RBs last year with 204 air yards, and then Saquon Barkley was second with 98. McCaffrey, despite barely playing in 2024, was actually fourth, not including Kyle Juszczyk (4-3-21), who you may notice in the graphic above I just put in the WR/TE category because the relevant stats for him are all the receiving ones, and he’s pretty clearly more of a TE than a traditional RB when utilized in pass concepts, regardless of his positional designation. Anyway, McCaffrey is back at it again this year, with at least 20 air yards in all five games so far, totaling 151 through five games. He’s going to go well beyond Johnson’s league-leading number from last year, and while we’re seeing RBs hitting for vertical plays in some big spots around the league, there aren’t any other RBs anywhere close to CMC’s consistency in this regard. The outcome is it almost doesn’t matter that he’s rushing poorly, averaging just 3.1 yards per carry. The 49ers actually went with a +4.2% PROE in this one, almost certainly because they can get the ball to their talented back through the air in more effective ways than they can get him into space on the ground right now.

I probably should have been more optimistic on Kendrick Bourne (11-10-142) in Input Volatility last week, because I mean if the guys you’re competing for routes with are Marquez Valdes-Scantling (3-1-9) and Skyy Moore (1-1 rushing), you’re probably in great shape to consolidate. As I’ve mentioned over the past couple weeks in both that column and Stealing Signals, Bourne is at least vaguely decent. He’d already gotten enough playing time after years in the Kyle Shanahan system earlier in his career with the 49ers that his rise to a key role shouldn’t have been surprising — even despite not signing with the team until after Week 1 — and Mac Jones is better than his status as a backup QB suggests (while still probably not being a great starter or anything), so it was one of those things for me where watching it, it wasn’t exactly a surprising outcome. Like, I was surprised by Rico Dowdle, which we’ll talk about later. For Bourne, I was just annoyed I didn’t think through it well enough. Some of that was having Bourne as a Signal after Week 3 only for him to have a tough Week 4, but then more opportunity opened up. I just sort of expected the 49ers to do terribly, but that was probably not the way to think about a Shanahan-McVay matchup, and is obviously not how it went.

Jake Tonges (11-7-41-1) also got a ton of volume as Jones threw 49 passes with the 49ers running a whopping 82 plays, both aided by the extra period. Demarcus Robinson (7-3-39) still managed to do very little. Juszczyk was the only other vaguely decent receiving game option, but it was mostly CMC and Bourne, with Tonges as the checkdown guy. Tonges did run a season-high 76% routes while Luke Farrell (2-1-8) moved backward to 27%.

Kyren had a much better game than his late fumble suggests, which his +17 RYOE and 10 HVTs do a better job of capturing. McCaffrey’s 11 HVTs tied for the week high with Jonathan Taylor, while Kyren was the only other guy with more than 7. Presumably because of how good Kyren was, there was less room for Blake Corum (1-13, 2-0-0), who played just 9% of the snaps after sitting between 24% and 31% over the past three weeks. Corum did have another drop as he continues to struggle when getting chances in the passing game, but I think the biggest reason his role was limited was Kyren just looked great from the jump, and McVay leaned into that.

Puka Nacua (12-10-85-1) and Davante Adams (11-5-88) also both got huge volume, as Matthew Stafford also threw a ton of passes, at 47. L.A.’s PROE of +10.8% was second highest on the week, and they totaled 528 air yards to lead the week. Just broadly, it was awesome to get a game where both QBs threw 45+ passes for over 340 yards through the air. Nacua continues to be a star, while Adams continues to work off that.

Terrance Ferguson (1-1-21) got out there, catching a slot fade for the first catch of his career, which was nice to see, although Davis Allen (2-2-24) and Colby Parkinson (1-0-0) were still both involved with Tyler Higbee out. Ferguson ran just 3 routes.

Tutu Atwell (4-2-72) and Jordan Whittington (3-2-33) were in their rotational roles. For deeper leagues, Whittington is another Malik Washington-type stash as a handcuff who could really consolidate volume if it came to that. (Obviously, the Washington thesis didn’t hit this week.) Over a two-week stretch early last year, Whittington saw 18 targets and caught 13 balls while playing over 90% of the snaps both games.

Signal: Christian McCaffrey — 151 air yards this season (most for a RB by a mile); Kendrick Bourne — 82% routes, 11 targets, 28% TPRR (he’ll be sensitive to who is active among other WRs and TEs, but there’s a short-term Signal here that he clearly has the coach’s and Mac Jones’ trust, and should run plenty of routes); Jake Tonges — 76% routes (gap in routes between him and Luke Farrell is spreading, which definitely makes him more viable until George Kittle returns); Kyren Williams — 10 HVTs (the 91% snaps may not stick, although it’s not his first foray into 90%+ waters, but there’s still a clear No. 1 RB trust here)

Noise: 49ers — 82 plays, 49 pass attempts (both led Week 5, through Sunday, and both were aided by overtime, among other things); Rams — +10.8% PROE, 528 air yards (both way above season averages); Blake Corum — 9% snaps (felt mostly like a hot hand thing with Kyren Williams playing really well in a big divisional matchup, but it was a reminder Kyren’s the clear No. 1)

Vikings 21, Browns 17

Key Stat: Quinshon Judkins — +110 RYOE for the season (third highest in NFL), 311 yards after contact (fourth highest in NFL)